Plantation

Under suitable climate, rainfall and environmental conditions, coconuts can germinate and grow into coconut palms and start fruiting after three years. This chapter is an introduction to the basics of cultivating coconut palms.

Varieties

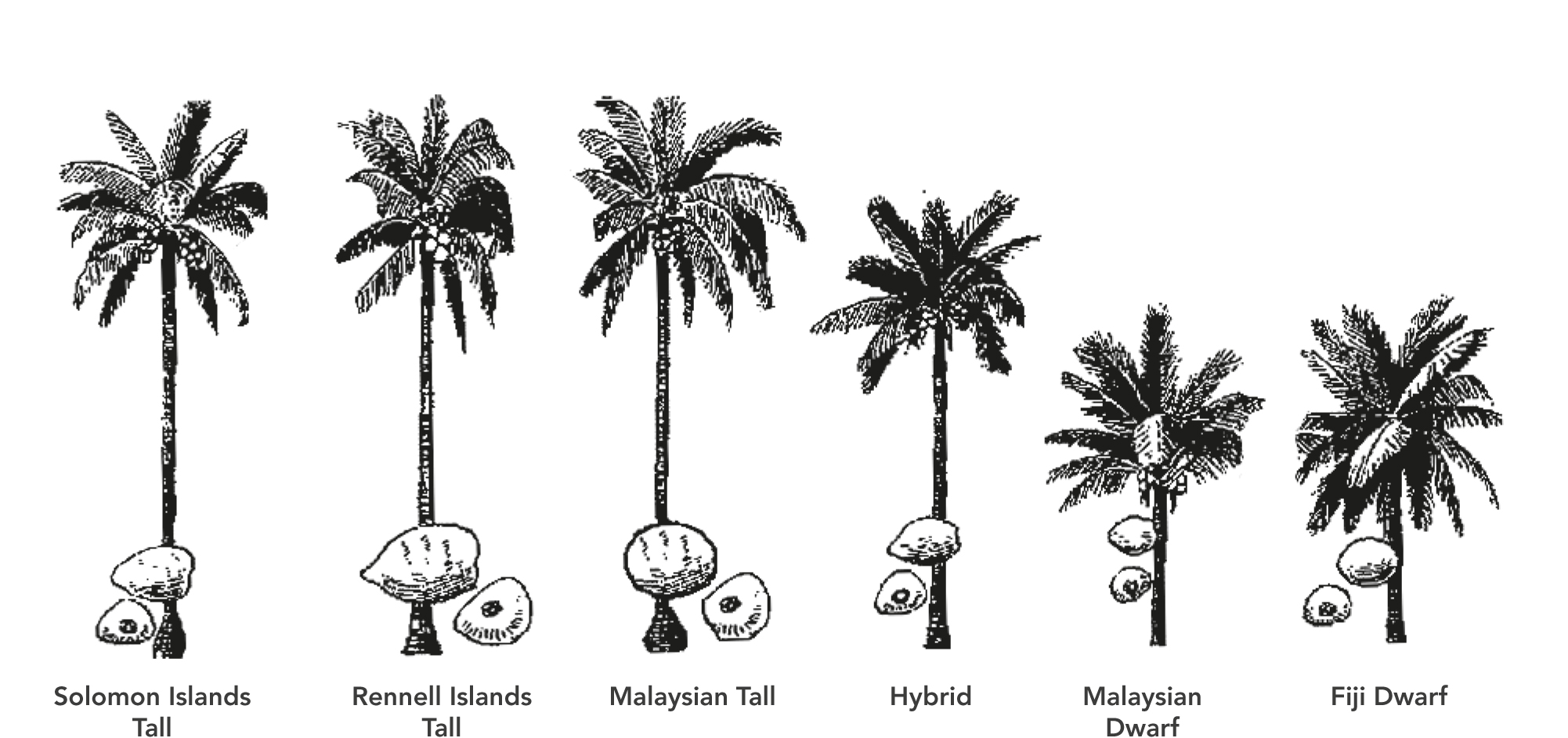

Coconut palms can be classified according to the size and stature of the palm, and are referred to as Talls and Dwarfs. They are also monoecious. In other words, they consist of male and female flowers on the same inflorescence (spadix) that develops within a woody spathe. Depending on the variety of the coconut trees, the male and female flowers develop at same or different times. As the coconut tree is propagated by seed, they are subjected to some variations which can be distinguished in the trees, fruits and leaves. As such, there are hundreds of vernacular names for the coconut types (Figure 4.1).

Tall coconut palms

Tall coconut palms are usually cross-pollinated and are subjected to the most variations. They are classified by the location where they are grown, assuming that some uniformity in the population is developed in one location across several generations, adapting to drought, high rainfall, alkaline soil or resistance to various insects and diseases long established in the specific location. This is why they are sometimes classified as West African Tall, Malayan Tall and such.

Tall coconut palms have longer economic lives than Dwarf trees, typically about 60-80 years, and can live up to 100 years old under favourable conditions. They also have larger fronds than Dwarf trees, so fewer Tall coconut trees can be planted per hectare of land. Tall coconut palms are also fairly resistant to diseases and pests, except some virus diseases, and thrive under different soil conditions. After six to eight years of planting, Tall coconut palms will begin to bear fruits.

Dwarf coconut palms

Dwarf coconut palms are mostly self-pollinated, and have fewer variations compared to Tall varieties. They are classified by the colour of the coconut fruits produced. As the name suggests, Dwarf coconut palms are smaller in stature than Tall varieties.

Dwarf coconut palms have shorter economic lives than Tall palms and only live up to 60 years old. With smaller fronds, more Dwarf coconut trees can be planted per hectare of land. Compared to Tall coconut trees, Dwarf varieties cannot adapt as well to different soil conditions, and are more susceptible to diseases, although they do show good resistance to some virus diseases. However, they begin to bear fruits earlier, after only three years of planting. At about 10 years old, they come into regular fruiting. Similar to Tall varieties, the bigger the coconuts, the lesser number of fruits found per bunch.

Hybrid coconut palms

Hybrids are inter-varietal crosses between two morphological forms of coconut trees. In particular, hybrids from Dwarf and Tall, Tall and Tall varieties also produce high-yielding coconut palms. In general, hybrid coconut palms are more superior in terms of quality and quantity of copra production. They also contain the greatest amount of copra per nut. As such, they are usually selected for commercial planting.

The hybrid crosses between Dwarf and Tall varieties have exhibited marked hybrid vigour by having the advantages found in both palms. As such, high yielding hybrid coconut trees are resistant to environmental stress, including drought and diseases. They also bear fruits after three to four years of planting. Compared to Dwarf and Tall varieties, hybrid coconut palms have more nut yields and higher copra production (Figure 4.2). The copra and oil produced are also of better quality.

Agronomic characteristics of coconut production

Life cycle of a coconut

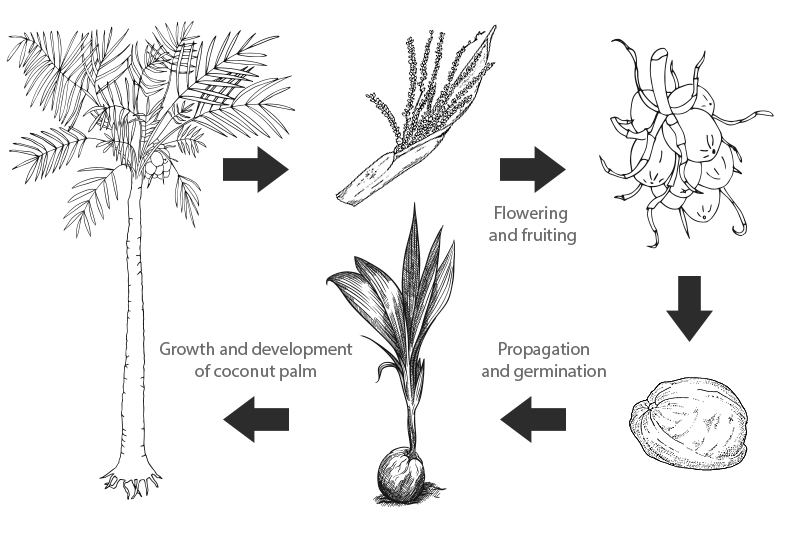

The agronomic characteristics of coconut production can be mapped out by the life cycle of a coconut (Figure 4.3).

Flowering and fruiting

Under favourable conditions, Tall coconut palms start flowering after planting for five years (three years for Dwarf), while the fruit fully ripens after 11-12 months.

Usually, only 30-40% of the fruits are carried to full term, while most are aborted within three months of pollination. The palm produces 12-15 inflorescences (spadices) each year at fairly regular intervals. This means that, every month, a new bunch of coconuts are formed. They continue to grow on the coconut tree until they are ready for harvest, or drop from the tree for propagation and germination. However, the number of female and male flowers per spadix varies, depending on the variety of the coconut tree.

Germination and propagation

Propagation is done by means of the coconut fruit, which has no dormancy and requires no specific treatment for germination. However, the speed of germination varies within and among coconut ecotypes and varieties.

Generally, 90% of seed fruits will germinate. The remaining 10% is usually discarded, failing to germinate due to the pathogenic infection of the seed interior caused by the fracture of the shell, after sprouting in the first three months.

During germination, the coconut haustorium, starts to develop. It is a sweet, spongy mass (cotyledon) which dissolves and absorbs the endosperm. As it develops, the haustorium depletes both the coconut water and kernel, which facilitates root and shoot growth in a germinating coconut (Figure 4.4). Under the right conditions, this germinated coconut will grow into a seedling (Figure 4.5).

Scientific and technological advances now allow for in-vitro collection of the coconut embryo, which can be employed in the exchange of plant materials across countries for propagation and breeding purposes (Engelmann et al., 2011).

Propagation by seed nut

Seed nut collection

Seed nuts may be collected throughout the year as and when they have reached the desired maturity level. When seed nuts mature, the husk loses moisture, while the exocarp (skin) starts to turn brown. When shaken, the fruit produces a sloshing sound. This indicates that the volume of coconut water in the cavity is decreasing.

After pollination, seed nuts usually take 12 months to ripen, around which time they start to fall from the trees. However, when the seed nuts are collected by picking off the ground, the identity of the female parent is difficult to establish. As such, the fruit is usually picked directly from the palm, so that the female parent can be identified for seed nut production.

Seed nuts should be selected from a block of uniform palms producing an average of at least 1,500 nuts per ha every 45 days. This is equivalent to an annual 2.8 tons of copra per ha. Within this block, the selected mother palms should have at least 40-50 full-sized nuts, anytime of the year under ordinary farm conditions (Magat, 1999).

Seed nut storage

Coconuts have no dormancy period between seed nut harvesting and germination. Therefore, it is not advisable to store fruits over extended periods of time. For varieties with cultivars that germinate early, such as Malayan Talls, immediate planting with no storage period is advisable. For varieties which are slower germinators, such as West African Talls and most Polynesian types, seed nuts may be stored for up to a month with no ill effects, as long as the coconut water in the cavity does not dry out. Alternatively, seed nuts may be picked when they are 11 months old and stored in a dry cool place for longer time periods. To hasten germination, partially or completely brown seed nuts can be stored in a ventilated or open shed for three to four weeks.

Seed nut planting

Coconuts do not require pre-planting treatment, so seed nuts can be planted directly. To facilitate seedling selection when there is a large quantity of seed nuts, a two-stage nursery may be used (Figure 4.6).

In the first stage, the germination bed allows seed nut selection based on the speed of germination (Figure 4.7). The early germinators are usually the best performers, while the slowest germinators (about 20-30% from the total seed nuts) are discarded.

In the second stage of the nursery, seedlings are grown to an acceptable size for out-planting. Those which display abnormal attributes are culled. Here, seed nuts are laid flat in rows, with two- thirds of the nut buried in coarse soil. Upon germination, nuts are pried out, trimmed of exposed roots, and planted back in the field.

Transplanting

The best time to transplant seedlings is at the onset of the rainy season. Seedlings should be 8-10 months old. Eight month old transplants give a better idea of their general growth and development. Differences in vigour are best seen when the seedlings are still too young to be moved, with the majority of their leaves still succulent.

Before transplanting, each hold should be applied with fertilizers mixed with soil. In addition, a small amount of organic matter like coconut husks can be placed at the bottom of the hole and covered with soil, leaving about one-third free for the seedling nut to ‘sit’.

For polybagged seedlings, the polybags are first removed, then the seedling is transplanted. The hold should be covered with loose topsoil, slightly firmed at the base of the crown. The top of the nut must be about 5-8 cm below the ground level. Deep planting might suffocate the bud, while the shallow planting might cause the planting material to bend, sway or lean during heavy rains and windy days. A slight depression towards the base of the crown must be provided to trap rainwater (Santos et al., 1995).

Propagation by coconut embryo culture

For propagation by coconut embryo culture, two coconut embryos in vitro collecting protocols have been established. One consists of storing the disinfected embryos, while the other includes in vitro inoculation of the embryos in the field.

In the former, a cylinder of solid endosperm containing the embryo is removed and stored in a potassium chloride solution for transporting to a laboratory, where the cylinders are disinfected again and the embryos extracted. These are placed in a solid embryo culture medium in a culture tube, and inoculated in vitro under sterile conditions.

In the latter, in vitro inoculation of the embryos in the field follows steps similar to storing disinfected embryos. However, instead of being stored in potassium chloride solution, the cylinder of endosperm is directly placed in a Petri dish. The embryo is extracted on the field inside a wooden box, which provides some protection from external contaminants. Then, it is rinsed again and inoculated to a solid embryo culture medium. Next, the tube is transported to a laboratory where the embryo is allowed to grow on the culture medium.

When the first true leaf is visible and the root system starts developing at least one root with ramifications, the plantlets are transferred to light conditions. Thereafter, plantlets are transferred to large tubes containing fresh medium every 4-6 weeks.

When plantlets display 3-4 unfolded green leaves, they can go on to acclimatisation after 6-7 months of initial inoculation. At this stage, plantlets are removed from culture tubes and planted in the greenhouse where soil nutrition and quality are controlled. After two months, they are then transferred to plastic bags filled with forest leaf mould mixed with sand before they are planted in the field.

GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT OF COCONUT PALM

The most rapid growth occurs between the second and fifth year of planting a coconut palm. A stem appears under the crown after growing for 3-4 years, and stem elongation reaches 30-50 cm annually, but slows down in older palms which are 40 years and older. After the sixth year, fruit production increases at the expense of vegetative growth. Thereafter, the coconut tree experiences fairly constant growth as yields are sustained over the next 40 years, and palm age can be roughly gauged from the length of the stem.

Agroecology - conditions required for growth

Soil

Coconut prefers fertile and adequately drained soils with a minimum depth of 75 cm, with high water-holding capacity (at least 30% clay content). A wide range of soil textures (sand-clay) is suitable for coconut production. The palm tolerates soil pH from 5.0-8.0. For optimum growth, a pH range of 5.5-6.5 is ideal (Magat, 1999).

Rainfall

As one of the thirstiest denizens of the plant kingdom, water plays an indispensable role in the successful cultivation of coconut palms. As such, it is strongly advised that coconuts be planted at the start of the rainy season, or under weather conditions with a rainfall of 1500-2300 mm evenly distributed throughout the year.

For profitable cultivation, total rainfall of 1800-2000 mm or more per year or 150 mm per month (4-5 mm per day), evenly distributed throughout the year is ideal (Magat, 1999). However, coconuts can still grow normally even with less rainfall, provided there is enough soil moisture or a high water table with good drainage. This is because the coconut palm requires large quantities of water to grow well, and water constitutes about 50% the total weight of fresh coconuts.

Generally, the coconut palm absorbs 24 litres of water each day, and the daily loss of moisture from mature coconut palm varies from 28-74 litres per day. However, the coconut does not like being waterlogged, and coconut palms will not survive more than two weeks of surface water logging.

Relative humidity

For normal growth and high yield, the relative humidity should be 80-90% and must not go below 60%. A persistently high humid condition is not suitable for the palm as it favors the rapid spread of Phytophthora disease (fruit rot or bud rot), a fatal disease commonly observed in yellow, red or orange dwarf varieties (Magat, 1999).

Latitudes, altitudes and salt

The coconut thrives in the tropics between latitudes 23°N and 23°S, at low altitudes not exceeding 600 m, where the temperature is between 22-34°C, with a mean temperature of 28°C.

Ideally, the relative humidity for coconuts to thrive should be more than 60%. There should also be no prolonged soil water deficit and excessive soil salinity. As coconuts are semi halophyte, they can grow in solutions where roots come into constant contact with salt concentrations of up to 0.6%. Therefore, it is possible to temporarily use sea water for irrigation purposes without any ill effects. However, an exclusive use of sea water is detrimental to the growth of coconuts, especially young trees.

Fertilizers

Salt fertilizer can also be applied to improve yields. In addition, they are environmentally friendly.

The use of sodium chloride (NaCl) or common salt as fertilizer is a practical mean of increasing coconut production. Salt is the cheapest and best source of chlorine to increase copra weight per nut and copra yield per tree. Generally, bearing palms are fertilized annually in areas with almost uniform rainfall distribution. In areas with distinct wet and dry seasons, uneven rainfall distribution, and those with sandy soils, fertilizers are best applied every six months. In a long- term study of salt application, 1.5 kg NaCl/tree per year is considered to be most effective and economical to increase copra weight/nut and copra yield (per tree and per hectare). Split application is done at the pre-bearing stages of palms, equivalent to 1-4 years. This practice helps reduce the loss of fertilizer nutrients through leaching and run- off, which makes the use of fertilizer more effective (Magat, 1999).

The use of multi-nutrient fertilizers (MNF), such as Nitrogen- Phosphorous-Potassium (NPK)-Sulphur-Sodium-Chlorine-Boron, is even more effective. This can increase yield by another 20%, 33% and 66% above that of salt-fertilised palms in the first, second and third years respectively (PCA, 2010). More importantly, the use of MNF can help to prevent mineral deficiency, which can lead to retarded root growth, delayed flowering, ripening of nuts and poor leaf health. In turn, these may result in smaller fruits produced and lower overall yield.

Planting systems

Monocrop or pure palms are planted at a density that allows the tips of horizontally held mature leaves to touch. The planting density is about 7-8 m spacing for Dwarf palms, 8-8.5 m for hybrids and 9-10 m for Tall palms. This is because the crown size of Tall palms are approximately 30% larger than hybrid and Dwarf varieties. This results in about 115-236 palms/ha under triangle system, or 100-200 palms/ha under square system.

Considering the same distance of planting, the triangular system can accommodate 15% more palms than the square system. As a guide, Table 4.1 shows the population and planting density under typical square and triangular systems of planting (Magat, 1999).

Yields

Yields vary from place to place. In general, commercial monocrop plantings out yield those in home gardens. Higher yields are obtained when there are more inputs, such as proper management, maintenance and regular fertilization. Annual yields range from 15-20 kg of copra or, depending on the fruit size, 50-80 fruits per coconut palm.

Competition

Coconut competes well with most plants for nutrients and water. However, its growth and yield slows in the presence of aggressive grasses such as the Imperata cylindrical. Pasture grasses, including Ischaemum aristatum, are commonly grown under old palms for cattle grazing. In general, coconuts grow poorly in shade. For instance, seedlings planted under older palms or other trees can take up to 10 years to flower with low yields.

For maximum productivity, all weeds that compete with coconut for nutrients, water, or sunlight should be suppressed. However, keeping the soil bare is not always a good management practice because apart from being laborious, it increases erosion risks and nutrient loss, and causes humas. Therefore, weeding may be done manually or mechanically. Animals can also be allowed to feed on them. However, it is better to leave about 1.0-1.5 m around the base of the palms uncropped. In addition, to minimise soil water loss during dry season and the growth of weeds, mulching with two layers of coconut husks around the base of coconuts can be done (Magat, 1999).

Pests and diseases

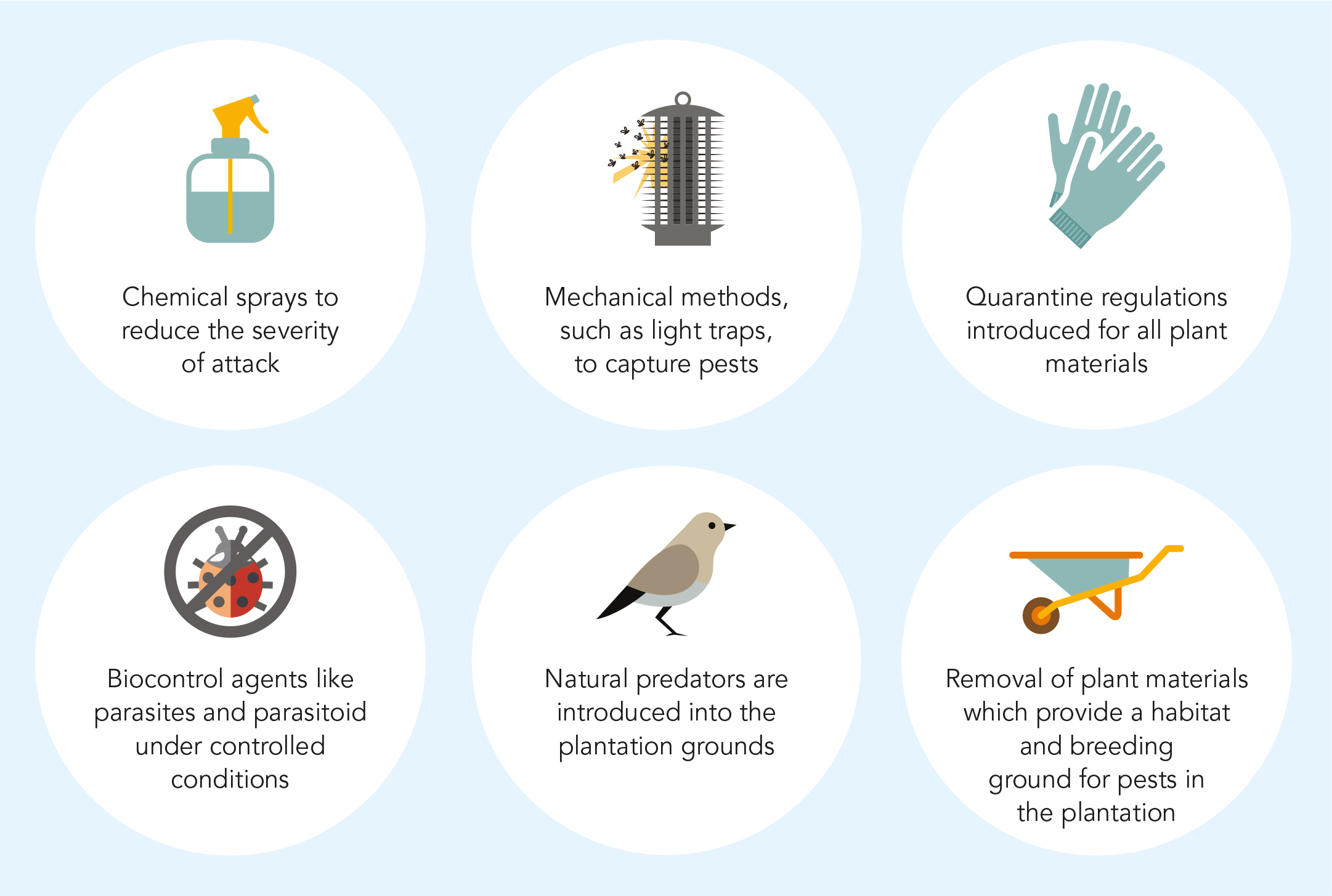

Coconut yield is susceptible to various pests and diseases, which affects the quality of coconut production during their life span. They even cause the palm to die. Common examples are as follow:

Rhinoceros beetle, Orycts rhinoceros

Rhinoceros beetle (Figure 4.8 and 4.9) attacks coconut palms in all stages of growth especially young palms which can be killed.

Its entry hole is marked by chewed up tissues; feeding of the beetle is shown by bilaterally symmetrical triangular cuts on the youngest open frond.

Photo courtesy of Asian and Pacific Coconut Community (APCC)

Nematode (worm), Radopholus similis

The burrowing nematode (worm), attacks the coconut root zone. Symptoms include main roots showing lesions and rotting as the nematode penetrates delicate regions behind the root cap.

Eriophyid Mites, Aceria guerreronis Keifer

Eriophyid Mites are so minute in size that they are not visible to the naked eye. Measuring 200-250 microns in length and 20-30 microns in width, they remain underneath the periyanth (cap) of the coconut and injures by feeding on the soft paranchymatic tissues.

Visible symptoms are brown discolouration in patches of the husk. In severe attacks of the button sheds, setting percentage of coconut is very poor. Coconuts are deformed and undersized, with poorly developed kernel and husk.

Red palm weevil, Rhynchophorus ferrugineus

The larvae of the Red palm weevil (Figure 4.10) can tunnel into the trunk of coconut palms, destroying the entire cabbage at which time the young fronds wilt. This can eventually cause palms to die.

Infestation occurs when there are chewed fibres and reddish-brown sap oozing from entrance channel.

Coconut scale, Aspidiotus destructor Signoret

Coconut scale (Figure 4.11) attacks palms at all stages. Infested leaflets turn yellowish, due to numerous spots which mark the position of scales on the underside of leaflets. This reduces the vitality of young palms. As a result, there is low yield.